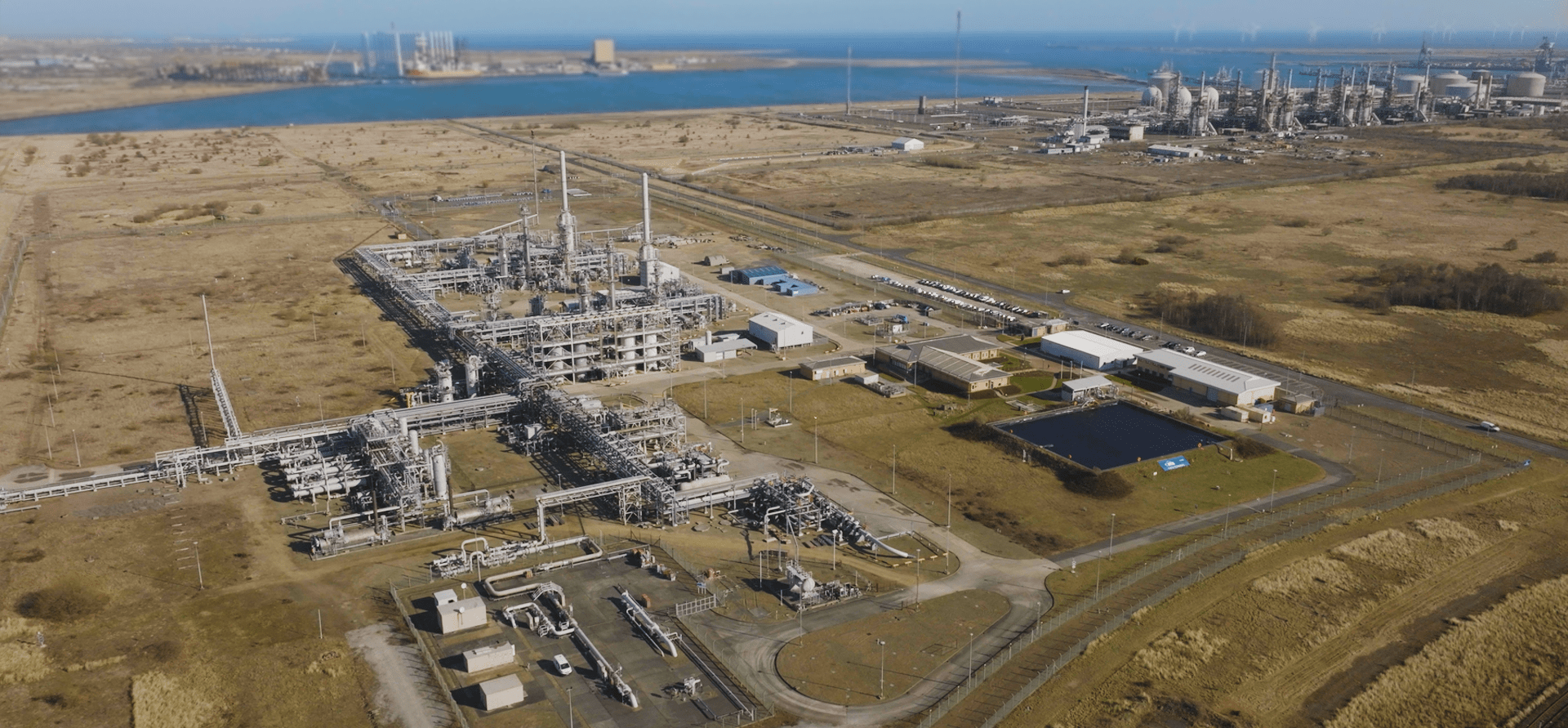

Every day, approximately 25% of the gas used to fuel the UK traverses a single 3ft-wide pipeline in Teesside. The terminal associated with the Central Area Transmission System can manage around 40% of the natural gas extracted from the North Sea, ensuring that it is treated and fed into the national transmission grid.

This facility also supports a substantial chemical complex, reputedly the second largest in Europe by manufacturing output, and assists other local heavy industries. Together, these operations emit up to 4.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide annually, rendering Tees Valley one of Britain’s most polluted industrial areas.

However, this site is poised for a greener—more specifically, bluer—future. Kellas Midstream, the operator of the terminal, believes that its location near industrial facilities and a proposed pipeline designed for sequestering captured carbon back into the North Sea positions it well to offer a cleaner energy alternative to unmitigated natural gas.

Through its H2NorthEast partnership with SSE, Kellas Midstream aims to generate 1 gigawatt of hydrogen by the dawn of the next decade. This output is sufficient to power around one million homes, contributing 10% to a 10GW target established by the previous administration for achievement by 2030.

The advantage of hydrogen lies in its zero carbon dioxide emissions when combusted. The H2NorthEast project intends to produce blue hydrogen by splitting natural gas into hydrogen and carbon dioxide, with the latter to be integrated into the East Coast Cluster. This initiative will capture emissions from the Teesside and Humber areas and securely store them in the Endurance saline aquifer located beneath the North Sea, managed by the Northern Endurance Partnership—collaboration between BP, Equinor, and TotalEnergies.

This cluster was among two chosen by the former government for the initial phase of carbon capture and storage development in Britain, which is emerging as a key technology to reduce emissions from high-polluting industries.

“Having access to feed gas, a CO2 storage option, and industrial customers willing to transition to hydrogen nearby sets up a solid framework for the project,” stated Nathan Morgan, the chief executive of Kellas Midstream.

Despite the enthusiasm surrounding hydrogen technology in recent years, most current low-carbon projects in Britain remain in the pilot or planning phases. These include ‘green’ hydrogen, produced through the electrolysis of water. Experts at Aurora, an energy consultancy, predict that significant progress in these projects won’t materialize until the late 2020s.

Funding poses a challenge, especially under a new government that, while showing support for hydrogen production, faces budgetary constraints. Two forms of governmental assistance are being considered to help equalize the cost discrepancy between natural gas and hydrogen. This support is set to function similarly to the contracts-for-difference model that assists renewable energy producers like offshore and onshore wind farms.

Last year, eleven green hydrogen initiatives, collectively capable of just 125 megawatts, were granted contracts that ensure a fixed price for their products over 15 years; a second round of funding announcements is anticipated soon. On average, the agreed price was £241 per megawatt-hour, compared to an average wholesale natural gas price of £74 per megawatt-hour as of the end of March, according to Cornwall Insights.

For projects leveraging carbon capture and storage, the previous administration allocated £20 billion through its cluster sequencing program. Two blue hydrogen projects, H2 Teesside and Vertex, have been confirmed under this program, promising a combined capacity of 4.5GW by 2030. H2NorthEast is planning to participate in a potential expansion of this program aimed at selecting additional projects.

The prices established for blue hydrogen projects, expected to be unveiled by the government in the upcoming budget, are projected to be lower than those set for green hydrogen initiatives.

“Currently, blue hydrogen will likely be more cost-effective than green hydrogen,” Morgan remarked, noting that it remains too early to assess the potential production costs at H2NorthEast. “All emerging technologies require some level of initial governmental support.”

He added that the significant decrease in clearing prices for contracts awarded to other renewable energy projects supports this argument. For instance, the average clearing price for offshore wind energy has more than halved since the first allocation round in 2015.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero emphasized, “Hydrogen will be integral to our ambition of establishing a clean energy economy while creating employment opportunities nationwide. Our national wealth fund is set to invest directly in hydrogen technology to position the UK as a global leader in this essential sector.”

Currently, H2NorthEast is in the engineering design phase. Its developers plan to make a final investment decision next year, with hopes to start significant capital investments within the next two years. The estimated cost to reach a 1GW capacity is around £2 billion, and the initiative aims to create an additional 100 jobs post-operation. Early agreements have been reached with potential partners in heavy industry and energy generation.

However, efforts like H2NorthEast are initiated amidst challenges from the North Sea, where ongoing production cuts are being considered due to increased government levies raising the taxation rate to 78%.

Additionally, there are ongoing concerns regarding the environmental impact of producing blue hydrogen, especially the emissions incurred during natural gas extraction. Morgan asserts that natural gas should be viewed as a transitional energy source as Britain strives for net-zero emissions. “At this point, we cannot practically afford to demand that only green hydrogen is produced; blue hydrogen is a necessary intermediate step.

“It’s critical to carefully evaluate our reliance on gas—both for its role in supporting renewable energy and as a feedstock for blue hydrogen production. We will continue to require gas.”